Time Shelter // Nostalgia in Society's Decline

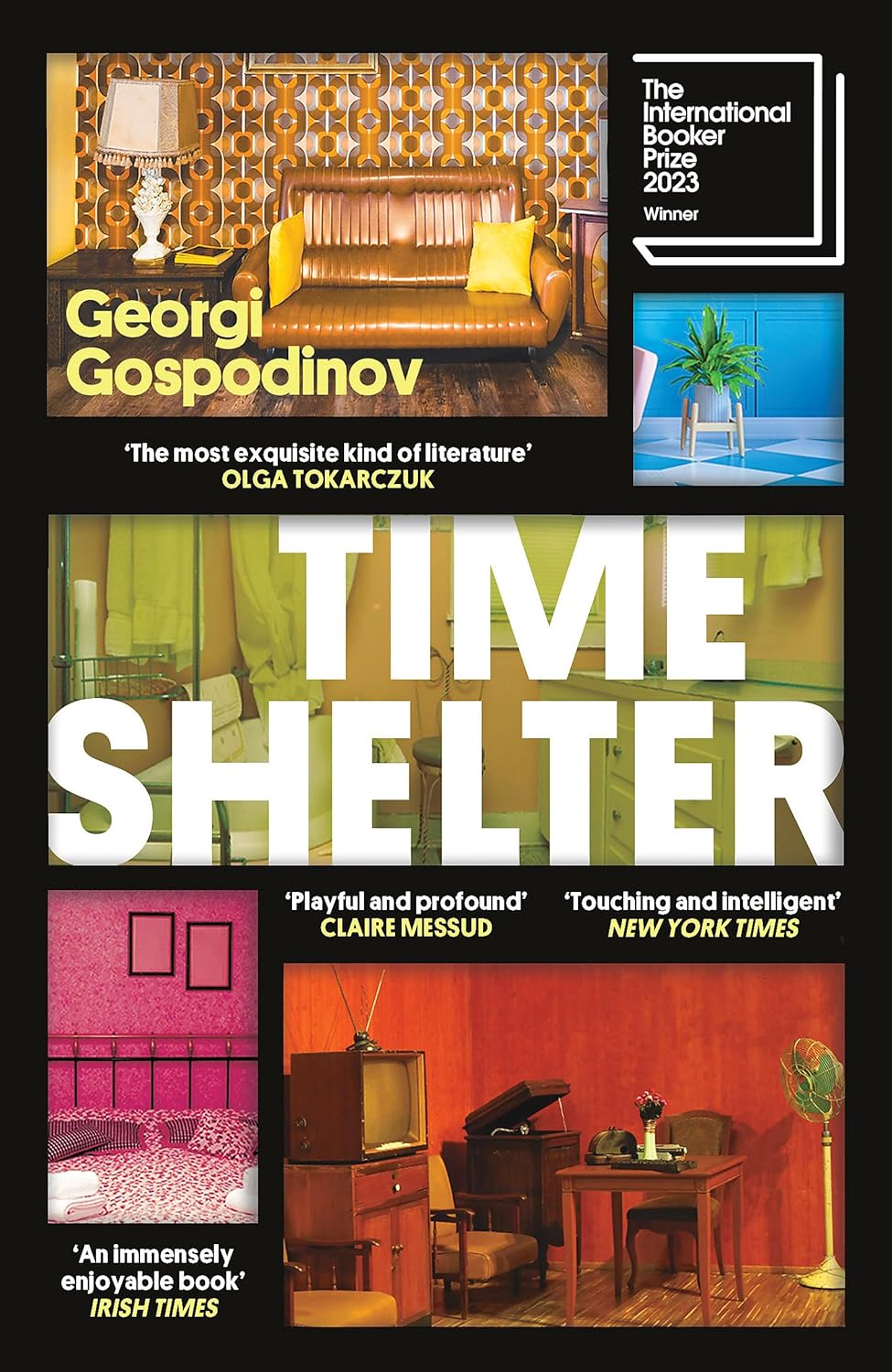

It’s been a year without much slack, and leisure reading has been hard to come by, so I’ve been listening to more audiobooks while I work around the house. This one was a recommendation from Hoopla, and I gave it a try: Time Shelter by Georgi Gospodinov.

From the description, I thought it would be a funky story about time travel. Instead, it was a tragic and often funny story about how Alzheimer’s disease affects individuals and societies, and I think it has something to say about this week’s kerfuffle over the US Senate’s dress code.

Time Shelter

Time Shelter is a Bulgarian novel, published in 2020 in Bulgarian then translated into English in 2022. The narrator’s relationship with a mysterious friend, Gaustine, is the core around which the story develops.

Gaustine pulls the narrator into a business venture: he is developing a clinic for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. He wants to provide them with the greatest possible comfort in their sunset years, so he designs his clinic to suit the progression of the disease. As the patients lose their most recent memories, they feel as though what they can still remember most clearly—the past—is actually the present. Gaustine’s clinic recreates the past so patients may feel more comfortable; if their surroundings match their perception, they may be more at peace than in a normal nursing home. He has rooms dedicated to the decades of the 20th century, providing a shelter for those who feel alienated from their own time. Along the way, the narrator injects wry observations from working alongside Gaustine.

It turns out that many people don’t want to live in the past as it was, but rather the past as they wished it had been—they want nostalgia, not memory. The patient who survived the holocaust is comfortable in the clinic of the past until a shower triggers her memory of a concentration camp.

There is a deceptively deep difference between memory and nostalgia.

Gaustine’s work is too good, and soon people come to his clinic who don’t suffer from Alzheimer’s disease. For many of them (and for the narrator), the fall of Communist regimes across Eastern Europe illuminated their early adulthood with revolutionary hope. That hope has shriveled in the decades since. They come to Gaustine’s clinic to escape their disappointment. They come to relive an old hope, not find a new one—to live again in a time when they didn’t know how things would turn out, when it seemed like plans and schemes and revolution could fulfill their dreams. Gaustine’s clinics multiply across Europe to meet the demand.

Reliving the past lets them pretend that they could have escaped a disappointing present.

Other entrepreneurs begin to notice the power of nostalgia. Where Gaustine has been experimenting with nostalgia as a numbing agent for the terminally-ill, others start to monetize it—and of course, the real money is at scale. At one point, the narrator stumbles upon a living history troupe staging a protest against a long-dead Communist regime. Another troupe of actors plays the secret police, brutally rounding up the protesters. Traditional ethnic garments make a comeback. Taxi drivers in Bulgaria swap out their modern taxis for the rustbuckets of the Soviet era.

Eventually, politicians discover that they can weaponize nostalgia.

Before long every country in Europe holds a referendum on which decade they should regress to. Several countries vote to return to the Cold War. The narrator describes a Soviet-era torture chamber preserved in a museum as a warning. Real screams echo off its walls again. Europe is an Alzheimer’s patient, losing its memory to nostalgia and desperate to placate its fears and disappointments by returning to an imagined past.

The Senate Dress Code

I think Gospodinov’s insights about the decline of individuals and societies provide a really interesting lens for thinking about last week’s news story about the US Senate ditching its dress code.

That choice was followed by a respectable amount of politicians being angry in front of cameras, and non-politicians expressed a good bit of outrage too.

On the one hand…

I think you could see that outrage pointing to a desire to make an institution—the US Senate in this case—seem as though it were as stable as we perceive it to have been in the past. (We’re talking nostalgia here, not memory—I think we tend to gloss over in our memories how volatile the Senate has actually been in its past.) In these troubled times, the argument goes, wouldn’t it be better to preserve at least the veneer of respectability the institution of the US Senate has enjoyed?

There are some worthwhile arguments against dropping the dress code—this is a move toward reckless individualism, away from sacrifice for the wellbeing of an institution; this is a move toward politicians building their own brands using political office instead of surrendering their brands to seek the wellbeing of their constituents; etc.

But I think you can make the case that those arguments value things (sacrifice for an institution, seeking the wellbeing of constituents) that aren’t inherently tied to a dress code. Instead, we think the dress code contributes to those good outcomes because we associate the dress code with respectability, and we associate the dress code with respectability because it reminds us of an imagined time when the Senate was more respectable.

It is fitting, then, that the Senate voted unanimously this week to adopt a dress code—four days before an impending government shutdown that will put 6% of America’s workers out of work. They have addressed the veneer of respectability and left the substance of their work undone.

This is what it looks like when a society trades its memory for nostalgia. It tries to placate its fears and disappointments, but it does not address them—in fact, I think you could argue that the placation is a tacit acknowledgement that the fears and disappointments cannot be addressed. This is the clinic a society enters to die in comfort.

On the other hand…

Gospodinov also has something to say about Sen. John Fetterman’s actions. During the week without a dress code, Fetterman’s choice of outfit wasn’t haphazard. It’s a signal, a sort of traditional ethnic garment: it identifies him as a man of the people, a member of PA’s blue-collar class.

Even his critics’ mocking—see that linked tweet above—plays into that signaling. Their mockery says that a person of this class doesn’t belong in the Senate, but it takes for granted that he is of the class he’s dressed up as.

His roots aren’t blue collar. He’s not depicting himself, but chill. He’s dressing up as his voters.

In Gospodinov’s story, he’s one of the actors dressed up as a counter-revolutionary. He’s reminding his voters of that precious moment in the past when elected representatives were really men of the people.

Thing is, that moment never happened.

But there’s a deceptively deep difference between memory and nostalgia. And politicians can weaponize nostalgia (#MAGA), because living in an imagined past lets people pretend that they could have escaped an unwelcome present.

Comments

Post a Comment